Rubber infill in synthetic turfs

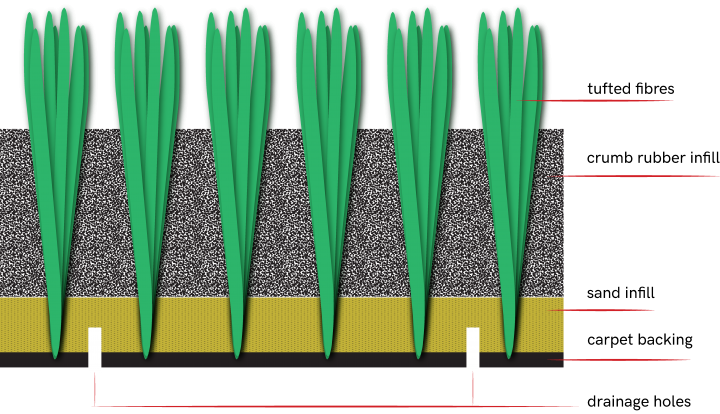

Crumb rubber (CR) is one of the most common forms of artificial turf infill and serves to keep the synthetic turf fibres upright, to weigh down the turf carpet and to make the turf field more shock absorbing. CR is made from used automotive tires that have been shredded into very small, smooth pieces, then rolled until all the sharp or rough edges are worn away.

There are more than 13,000 large synthetic turf fields in the European Union (data 2017) and even a higher number of mini-pitches. These pitches are mainly used for football. Compared to natural grass, these pitches allow year-round playing irrespective of the weather conditions. Because artificial turf tolerates intense playing, less fields and thus less land suffices to facilitate outdoor field sports.

In May 2021, ECHA published a follow-up study on substances (other than PAHs) in plastic and rubber granules and mulches used as infill on artificial pitches. It identified over 300 chemicals that could potentially be found in the infill material and created criteria to prioritize those that potentially pose the greatest concern.

ECHA therefore recommended that further assessments should be carried out on the following chemicals that could be harmful to people or the environment:

- Cobalt and zinc with potential risk to people’s health

- Cadmium, cobalt, copper, lead, zinc, 4-tert-octylphenol, 4,4´-isopropylidene diphenol (BPA), bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP), benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP) and benzothiazole-2-thiol with potential risk to the environment

The risks of PAHs to the environment also need to be examined in any future assessments.

The production of granulates as infill for artificial turf is able to process 21% of the end-of-life tires in Europe, approximately 600 million kg per year. In doing so it avoids an annual CO2 emission comparable with the amount that could be absorbed by around 30 km² of forest.

However, concerns have been raised regarding the potential health hazards and environmental risks of a broad spectrum of toxic substances known to be released from CR. Risks associated with CR differ depending on the exposure route as well as a variety of environmental factors, including precipitation, heating/cooling cycles, ozone, oxygen, and UV light exposure that can accelerate the leaching of toxic chemicals from CR.

The dispersal of rubber infill to the environment also adds to the problem of microplastic pollution.

An amount of 3000–5000 kg granulate per field per year is currently used as underpinning for a European proposal to ban rubber infill as part of the intended restriction on intentionally added microplastics in 2021.

Health risks

Over 300 chemicals have been identified in CR, of which nearly 200 are predicted to be carcinogenic and genotoxic.

Preliminary toxicity experiments with Daphnia magna indicate that CR water leachate causes immobility and mortality depending on leachate. These findings align with the acute toxicity of CR reported in aquatic model organisms, such as alga, daphnia, amphibians, and fish as well as soil invertebrates. However, the impacts of CR exposure to higher vertebrates, including humans, are unknown. To address this critical knowledge gap, researchers at the Department of Chemical Engineering, McGill University, Montréal developed an amniote vertebrate model to study toxic effects and mechanisms of CR toxicity.

Chicken eggs

Athletes and children are playing on artificial turfs. However, the health risk associated with exposure to crumb rubber (CR) from artificial turfs is unknown for higher vertebrates. Therefore, a Canadian study at the Department of Chemical Engineering, McGill University, Montréal, employed chicken embryo as a developing amniote vertebrate model to show that toxic leachate from artificial athletic turf infill impairs the early development of chicken, notably brain and cardiovascular system.

CR water leachate was administered to fertilized chicken eggs via different exposure routes, i.e., coating by dropping CR leachate on the eggshell; dipping the eggs into CR leachate; microinjecting CR leachate into the air cell or yolk. After 3 or 7 d of incubation, embryonic morphology, organ development, physiology, and molecular pathways were measured.

The results showed that CR leachate injected into the yolk caused mild to severe developmental malformations, reduced growth, and specifically impaired the development of the brain and cardiovascular system, which were associated with gene dysregulation in aryl hydrocarbon receptor, stress-response, and thyroid hormone pathways. The observed systematic effects were probably due to a complex mixture of toxic chemicals leaching from CR, such as metals (e.g., Zn, Cr, Pb) and amines (e.g., benzothiazole). The study points to a need to closely examine the potential regulation of the use of CR on playgrounds and artificial fields.

In June 2016, the European Commission asked ECHA to assess whether the presence of certain chemicals in the granules could pose a health risk. This request was driven by claims originating in the US where Amy Griffin , a former professional goalkeeper, had been collecting data on cancer cases among her fellow goalkeepers.

There were concerns of increased cancer risk to children playing on these pitches. As a result, several studies were kicked off in the EU and US.

ECHA assessed the health risks, looking at exposure through skin contact, ingestion and inhalation. The findings were published in February 2017, with ECHA concluding that there was a very low level of concern from exposure to the granules.

The risk of cancer after lifetime exposure to rubber granules was judged to be very low based on the concentrations of PAHs measured at some European sports grounds. These concentrations were well below the legal limits. Also, the presence of heavy metals, phthalates, benzothiazole and methyl isobutyl ketone were below concentrations that would lead to health problems. The findings noted that, where the rubber granules were used indoors, the volatile organic compounds released might lead to skin and eye irritation.

ECHA’s report highlighted some uncertainties that would warrant further investigation. For instance, there was a concern over how representative the studies were for the whole of Europe (given that samples were not taken from all Member States). The Agency, therefore, recommended among other things that people should take basic hygiene measures after playing on artificial turf to counteract these uncertainties.

In addition to ECHA's findings, the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) conducted a study on the health risks of rubber granules used in the Netherlands in early 2017, which confirmed that playing sports on these fields is safe. However, the study gave a recommendation to further reduce the legal concentration limits of cancer-causing PAHs in the infill material. The Dutch authorities submitted a restriction proposal with a specific concentration limit value for PAHs.

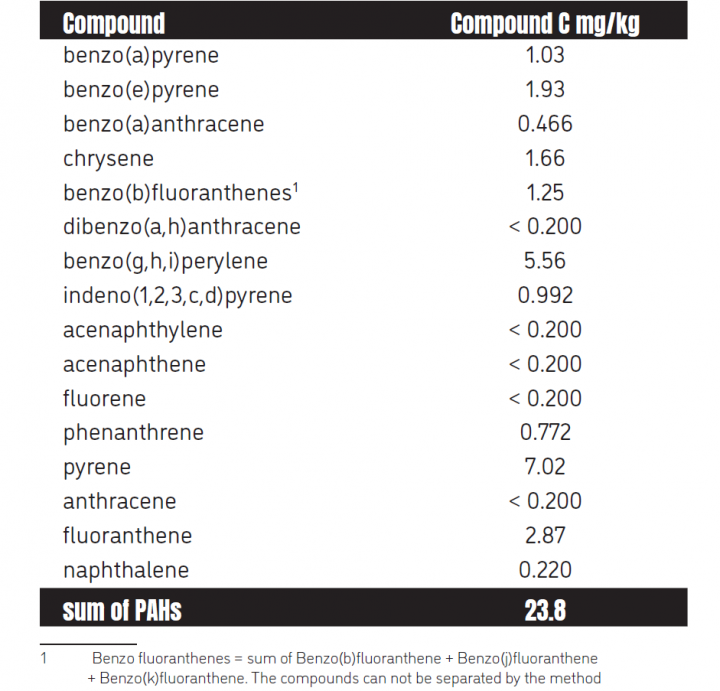

In 2017, Centexbel conducted a field test on recycled rubber granules sampled from a synthetic turf field in Flanders, Belgium.

Tests

Determination of PAH content

- Extraction method: Ultrasonic extraction with toluene

- Analytical method: GC-MS-MS

Results

- The concentration of the total sum of PAH’s (18) was 23mg/kg, within the limits of the legislation applicable at the time.

- The concentration of the 8 PAH’s that are now being restricted specifically for synthetic turf is 6.34 mg/kg. This value is also compliant with the regulation that will be applicable as from 10/08/22.

Restricting PAHs in granules and mulches

In July 2018, the Dutch authority RIVM proposed a restriction to limit the concentration of eight PAHs in granules or mulches used as infill material in synthetic turf pitches or in loose form for use in sports applications and on playgrounds. The legal concentration limits in force at the time of the proposal were 100 mg/kg for two of the PAHs (BaP and DBAhA) and 1 000 mg/kg for the other six (BeP, BaA, CHR, BbFA, BjFA, BkFA). RIVM considered these limits to be too high to ensure the safety of people, and especially children, playing on sports pitches and playgrounds.

PAHs are known constituents of both extender oils and carbon black used to manufacture vehicle tyres. They are known to cause cancer. Animal model studies link the group of chemicals to skin, lung, bladder, liver and stomach cancers. PAHs have also been linked with heart disease and poor foetal development.

The restriction assessed the risks from eight PAHs to professional footballers, children playing on the pitches, and workers involved in installing and maintaining the pitches and playgrounds.

The Dutch authorities recommended to lower the combined concentration limit for the eight PAHs to 17 mg/kg. The aim was to ensure that exposure to the PAHs remains at a low level also in the future and that the use of infill from imported recycled tyres is also regulated.

ECHA’s Committees for Risk Assessment (RAC) and Socio-Economic Analysis (SEAC) started their evaluation of the proposal in September 2018. A consultation on the proposal ran from September 2018 to March 2019. Subsequently, there was a consultation on the SEAC draft final opinion from June to August 2019.

The consolidated opinion of RAC and SEAC was sent to the European Commission at the end of 2019. RAC evaluated the risks of PAHs to people’s health. SEAC evaluated the benefits of the proposal to people’s health and the associated costs and other socio-economic impacts. Both committees agreed that – with a few modifications – a restriction proposal would be the most appropriate means to ensure that the cancer risk from PAH exposure remains at a low level for those playing on artificial sports pitches or playgrounds that use rubber infill or mulches.

The opinion proposed a concentration limit of the eight PAHs of 20 mg/kg.

The restriction was supported by EU Member States in December 2020 and adopted by the Commission in July 2021. It prohibits the placing on the market and use of granules and mulches as infill if they contain more than 20 mg/kg of the sum of the eight PAHs. Granules or mulches placed on the market also have to be batch labelled to ensure safe use.

The new rules apply in the EU/EEA from 10 August 2022.

It will make playing on artificial sports pitches and playgrounds safer and may help to ease social concerns and worries over playing on artificial sports pitches and playgrounds. The restriction will not affect existing fields immediately but will ensure that any infill material used for refilling the fields is below the new limit.

Environmental risks

Microplastic pollution

The rubber and plastic granules used on sports pitches are considered microplastics. Each year around 42 000 tonnes of microplastics end up in the environment when products containing them are used. Granular infill is the largest single source of pollution with estimated releases of up to 16 000 tonnes per year.

These granules can end up in our waters. They can also spread in the environment through snow clearing and other maintenance work.

Restricting intentional uses of microplastics

In January 2019, ECHA proposed a wide-ranging restriction on microplastics in products placed on the EU/EEA market to avoid or reduce their release to the environment. This restriction proposes two options to address the spreading of infill material from artificial pitches:

- a ban on placing on the market after a transition period of six years; or

- mandatory use of risk management measures (such as fences, brushes) to prevent the loss of infill from the pitches after a transition period of three years.

The proposal is now with the European Commission for decision making with the EU Member States. It is not yet known which option the Commission will present to the Member States nor what the final decision on the restriction will be.

Turf War explained/illustrated

turf war

noun: an acrimonious dispute between rival groups over territory or a particular sphere of influence.

"Turf War" was the first major exhibition by artist Banksy, staged in a warehouse on Kingsland Road in London's East End in 2003.